The Way Things Used To Be

Steven R. Cooper

Originally published in the Central States Archaeological Journal, Vol.55, No.4, pg.250

For more than one hundred and fifty years, collectors, amateur archaeologists, opportunists and the impoverished dug and removed artifacts from prehistoric graves in Arkansas. Although today referred to as looting and/or grave robbing, it was a legal practice up until 1991. Many ancient sites, including some large ones, were and/are still in private hands. These sites presented an opportunity to find the past and remove it from the earth.

The State Legislature of Arkansas passed Act 753 known as the Grave protection Act in 1991. While it addressed other issues, such as ownership of human remains, its main focus was to forbid any digging of prehistoric gravesites on private land.

The pictures presented in this article are of legal digging prior to the enactment of this law. The author, nor the Central States Archaeological Societies, suggests that any of these activities should be practiced today. They are now illegal, and those who knowingly violate the law should be prosecuted.

The author reviewed the pictures, the dates on the back of them, and has made all necessary inquires to make sure none of the activities pictured in this brief story are after the passage of the law or show illegal activity.

After the Civil War, there arose a large interest in the prehistoric peoples of the United States. As more land was cultivated and populated, more and more artifacts started turning up. The collecting of such things became a pastime for many people. Curio shops became a fixture in many towns offering exotic pottery, stone items and arrowheads. For many of the artifacts, demand far exceeded supply. Pipes, huge flints and other rare items have never existed in large supply. This was the beginning of the creation of fakes and reproductions.

However, there were ample amounts of pottery. The prehistoric Indians were superb potters, and buried literally thousands of pots across the state of Arkansas and other areas.

Where there is demand, there can also be profit. While many collected because of a passion for it, there were those who recognized there was money to be found in the ground. These became the first diggers, who then sold their finds to the Curio shops and collectors back in the Eastern United States. Museums, including the Smithsonian and Harvard, sent expeditions to obtain artifacts for their collections. Many of these expeditions utilized information from the local dealers and collectors to find the sites. They removed huge amounts of objects, especially pottery. And yet there still seemed to be no dwindling of the supply.

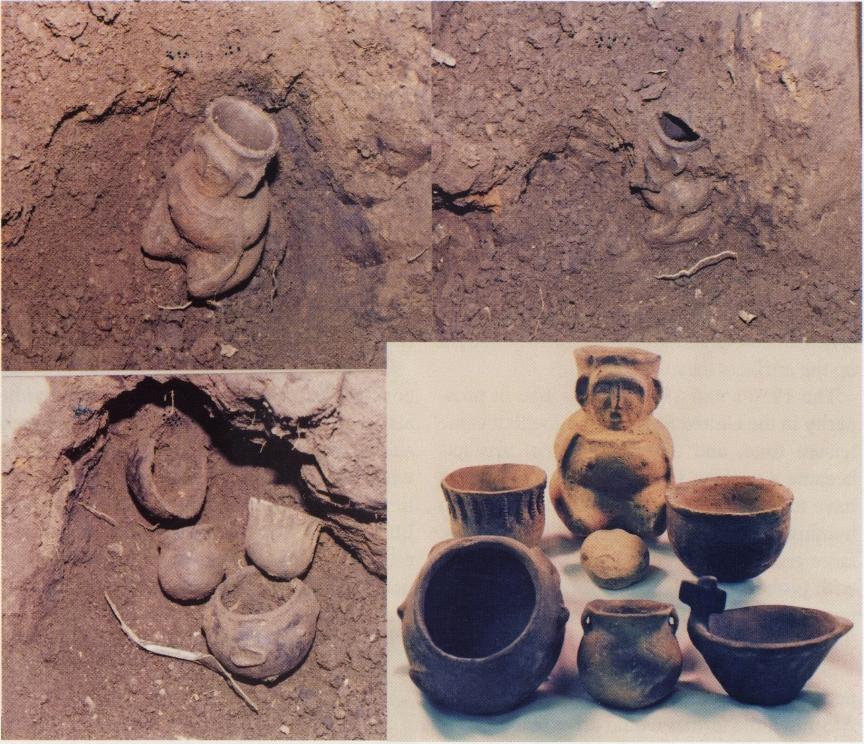

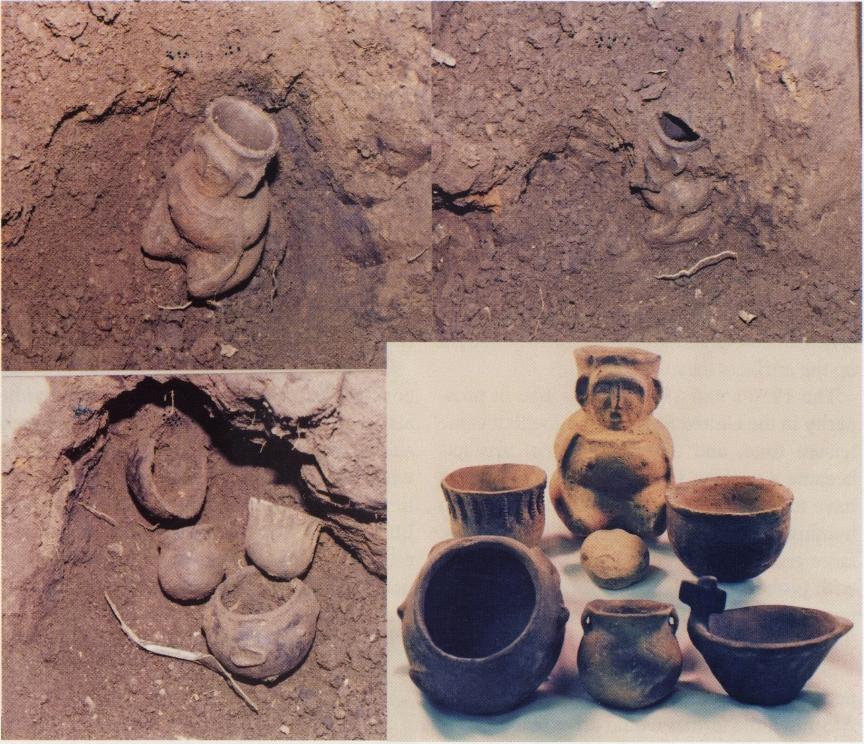

Above: A blonde/orange colored vessel in situ and after excavation by Larry Garvin at the Knappenberger Site in Mississippi County, Arkansas on March 9'", 1990. The vessel measures 8 inches tall and 9 ½ inches wide.

Above: A group of six vessels found along with a discoidal on November 15th, 1990 at the Austin Site in Mississippi County, Arkansas. The duck effigy was covering the human effigy vessel.

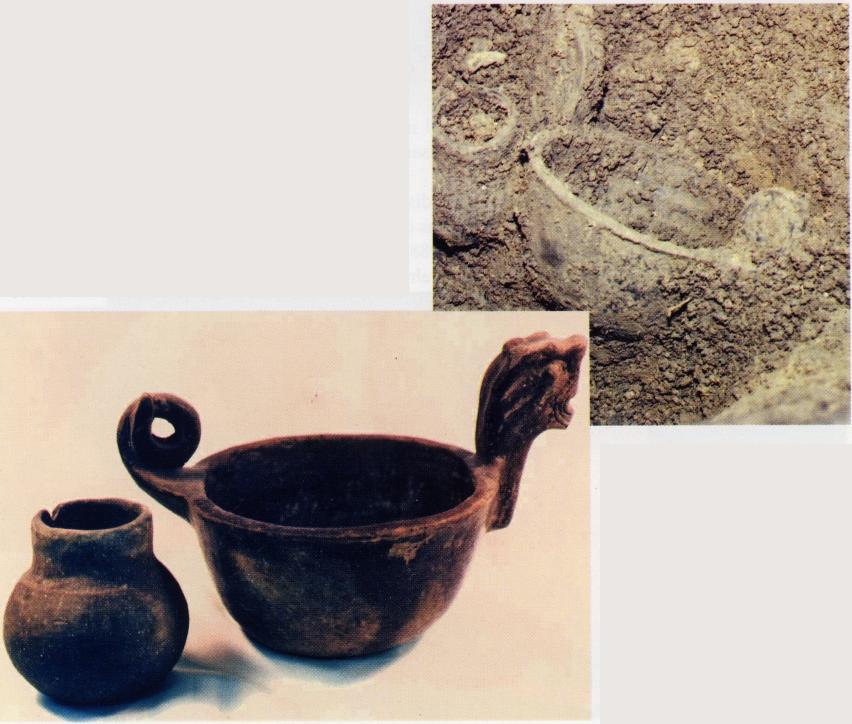

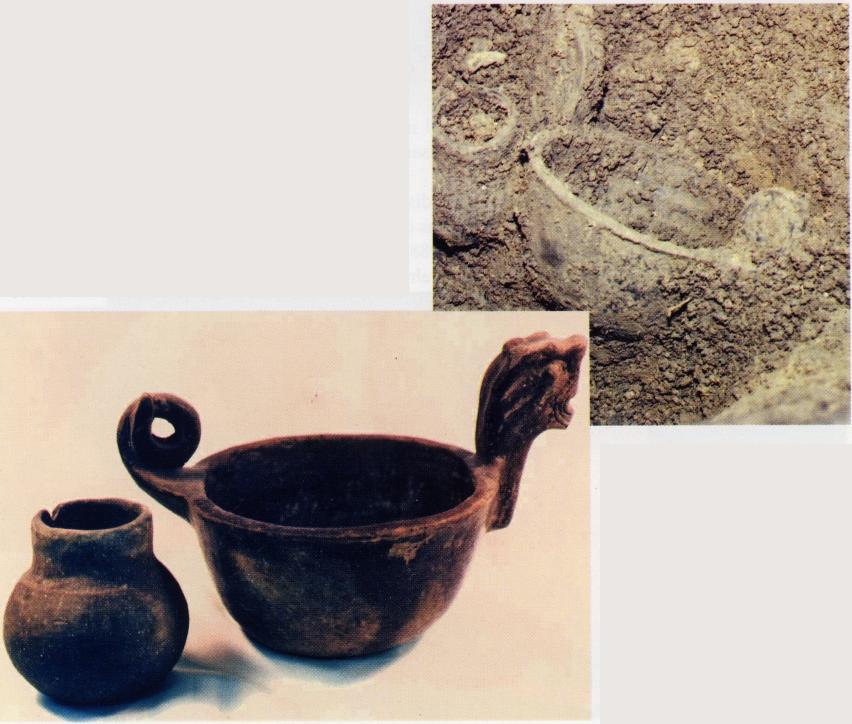

Below: Two vessels found together in March 1988 by Ron Stamm at the Crosskno Site, Mississippi County, Arkansas. The large red on buff bottle is almost 10 inches tall.

In the 1920's, a huge site was discovered in the Carden Bottoms in Central Arkansas. At that time, crops were failing and the farmers needed money. A literal "gold rush" for prehistoric pottery came about. Wagonloads were sold to dealers, collectors and museums. Many of the finds were spectacular effigy pots, and strangely, Caddo, Mississippian and even Quapaw pottery were found at this site.

The 1930's saw the arrival of the Great Depression. It was the direct cause of the creation of the Pocola Mining Company; known for it's "looting" of the Spiro Mounds Site in neighboring Oklahoma. These "diggers" were desperate to create wealth in a time of poverty. Collectors and museums quickly bought up the artifacts they uncovered.

The 1950's and 1960's saw a rise in prosperity in the United States. Along with it came leisure time, and the collecting of artifacts became a passion for many. Many collectors have told me that it was weekend sport to go hunting and digging for artifacts. In Arkansas, large groups would go to known sites. Armed with probes, shovels and assorted tools, pottery and other artifacts were removed by the thousands.

One collector related to me that there were perhaps twenty groups in a field at one time. At sunset, the farmer would drive in his Cadillac up to each group and collect five dollars from each. They were expected to fill back in the spots they had dug. I've heard stories where someone would spend a week and find only two pots. Other times twenty pots might be uncovered in one day.

While there are horror stories where some literally threw the bones in graves across the fields, the majority of collectors held respect for these ancient individuals. Most never disturbed or removed any bones.

While the stone artifacts survived well in the ground, pottery was never a sure thing. Many have probe holes. Many were what was known as "sack" pots, a whole pot that was removed from the ground in pieces. These needed restoration to make them whole again. Probably less than 10% of all pottery removed from the ground was undamaged and without need for repair.

One can discuss the archaeological pros and cons of these practices. Today, these individuals are referred to by such terms as pothunters and looters. But it must be kept in mind that what they were doing was not illegal at the time. It was openly done, and there was very little protest from the archaeological community. Many landowners encouraged the practice as a way to achieve extra income off of their land.

Above: Two Mississippian vessels found together at the Austin Site in Mississippi County by Larry Garvin on March 8th, 1991. On March 10th Governor Bill Clinton signed the Grave Protection Act and ended activities like this forever. The Cat serpent measures 9 1/2 inches from nose to tail.

All this changed in the late 1980's, with the rise of the American Indian Movement, and a fear that our archeological past might be destroyed. Modern methods are more concerned with the understanding of the past instead of just acquiring fine artifacts. With more than 100 years of prehistoric prospecting, there are thousands of artifacts in museums and private hands. The 1991 Grave Protection Act insured that the remaining archaeological resources would stay as they have been, buried and not to be disturbed. Modern methods will expand our understanding of the past beyond the artifact. But the artifacts of these ancient peoples still excite our imaginations and maintain public interest in the peoples of the past. The future of archaeology rests in the hands of public and private funding. If there is interest there will be progress. Hopefully the 21st century will enhance our understanding of these ancient peoples and help us to know those who lived here for thousands of years.

Used by permission of the publisher

To learn more about or to join the Central States Archaeological Society, click here: http://www.csasi.org/

Steven R. Cooper

Originally published in the Central States Archaeological Journal, Vol.55, No.4, pg.250

For more than one hundred and fifty years, collectors, amateur archaeologists, opportunists and the impoverished dug and removed artifacts from prehistoric graves in Arkansas. Although today referred to as looting and/or grave robbing, it was a legal practice up until 1991. Many ancient sites, including some large ones, were and/are still in private hands. These sites presented an opportunity to find the past and remove it from the earth.

The State Legislature of Arkansas passed Act 753 known as the Grave protection Act in 1991. While it addressed other issues, such as ownership of human remains, its main focus was to forbid any digging of prehistoric gravesites on private land.

The pictures presented in this article are of legal digging prior to the enactment of this law. The author, nor the Central States Archaeological Societies, suggests that any of these activities should be practiced today. They are now illegal, and those who knowingly violate the law should be prosecuted.

The author reviewed the pictures, the dates on the back of them, and has made all necessary inquires to make sure none of the activities pictured in this brief story are after the passage of the law or show illegal activity.

After the Civil War, there arose a large interest in the prehistoric peoples of the United States. As more land was cultivated and populated, more and more artifacts started turning up. The collecting of such things became a pastime for many people. Curio shops became a fixture in many towns offering exotic pottery, stone items and arrowheads. For many of the artifacts, demand far exceeded supply. Pipes, huge flints and other rare items have never existed in large supply. This was the beginning of the creation of fakes and reproductions.

However, there were ample amounts of pottery. The prehistoric Indians were superb potters, and buried literally thousands of pots across the state of Arkansas and other areas.

Where there is demand, there can also be profit. While many collected because of a passion for it, there were those who recognized there was money to be found in the ground. These became the first diggers, who then sold their finds to the Curio shops and collectors back in the Eastern United States. Museums, including the Smithsonian and Harvard, sent expeditions to obtain artifacts for their collections. Many of these expeditions utilized information from the local dealers and collectors to find the sites. They removed huge amounts of objects, especially pottery. And yet there still seemed to be no dwindling of the supply.

Above: A blonde/orange colored vessel in situ and after excavation by Larry Garvin at the Knappenberger Site in Mississippi County, Arkansas on March 9'", 1990. The vessel measures 8 inches tall and 9 ½ inches wide.

Above: A group of six vessels found along with a discoidal on November 15th, 1990 at the Austin Site in Mississippi County, Arkansas. The duck effigy was covering the human effigy vessel.

Below: Two vessels found together in March 1988 by Ron Stamm at the Crosskno Site, Mississippi County, Arkansas. The large red on buff bottle is almost 10 inches tall.

In the 1920's, a huge site was discovered in the Carden Bottoms in Central Arkansas. At that time, crops were failing and the farmers needed money. A literal "gold rush" for prehistoric pottery came about. Wagonloads were sold to dealers, collectors and museums. Many of the finds were spectacular effigy pots, and strangely, Caddo, Mississippian and even Quapaw pottery were found at this site.

The 1930's saw the arrival of the Great Depression. It was the direct cause of the creation of the Pocola Mining Company; known for it's "looting" of the Spiro Mounds Site in neighboring Oklahoma. These "diggers" were desperate to create wealth in a time of poverty. Collectors and museums quickly bought up the artifacts they uncovered.

The 1950's and 1960's saw a rise in prosperity in the United States. Along with it came leisure time, and the collecting of artifacts became a passion for many. Many collectors have told me that it was weekend sport to go hunting and digging for artifacts. In Arkansas, large groups would go to known sites. Armed with probes, shovels and assorted tools, pottery and other artifacts were removed by the thousands.

One collector related to me that there were perhaps twenty groups in a field at one time. At sunset, the farmer would drive in his Cadillac up to each group and collect five dollars from each. They were expected to fill back in the spots they had dug. I've heard stories where someone would spend a week and find only two pots. Other times twenty pots might be uncovered in one day.

While there are horror stories where some literally threw the bones in graves across the fields, the majority of collectors held respect for these ancient individuals. Most never disturbed or removed any bones.

While the stone artifacts survived well in the ground, pottery was never a sure thing. Many have probe holes. Many were what was known as "sack" pots, a whole pot that was removed from the ground in pieces. These needed restoration to make them whole again. Probably less than 10% of all pottery removed from the ground was undamaged and without need for repair.

One can discuss the archaeological pros and cons of these practices. Today, these individuals are referred to by such terms as pothunters and looters. But it must be kept in mind that what they were doing was not illegal at the time. It was openly done, and there was very little protest from the archaeological community. Many landowners encouraged the practice as a way to achieve extra income off of their land.

Above: Two Mississippian vessels found together at the Austin Site in Mississippi County by Larry Garvin on March 8th, 1991. On March 10th Governor Bill Clinton signed the Grave Protection Act and ended activities like this forever. The Cat serpent measures 9 1/2 inches from nose to tail.

All this changed in the late 1980's, with the rise of the American Indian Movement, and a fear that our archeological past might be destroyed. Modern methods are more concerned with the understanding of the past instead of just acquiring fine artifacts. With more than 100 years of prehistoric prospecting, there are thousands of artifacts in museums and private hands. The 1991 Grave Protection Act insured that the remaining archaeological resources would stay as they have been, buried and not to be disturbed. Modern methods will expand our understanding of the past beyond the artifact. But the artifacts of these ancient peoples still excite our imaginations and maintain public interest in the peoples of the past. The future of archaeology rests in the hands of public and private funding. If there is interest there will be progress. Hopefully the 21st century will enhance our understanding of these ancient peoples and help us to know those who lived here for thousands of years.

Used by permission of the publisher

To learn more about or to join the Central States Archaeological Society, click here: http://www.csasi.org/

Comment