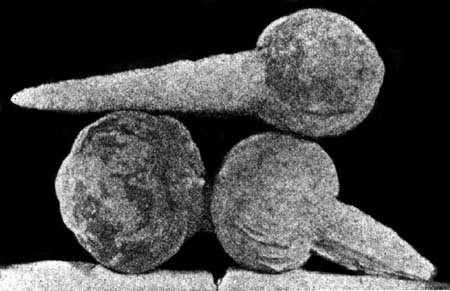

SAND SPIKE CONCRETIONS

These items, which you might mistake for some kind of club (if large) or charmstone (if small), are completely natural. They’re known as “sand spikes” and normally form in silt deposits as fine sand concretions cemented by calcite. The circumstances in which they are found may also falsely suggest that they have been deliberately buried in caches. Frequently you will find them in numerous clusters in secondary Pleistocene deposits, with the spike ends pointing away from an older formation they have been washed out of… sometimes hundreds of them, all uniformly oriented in a horizontal position, parallel to the boundary of an ancient shoreline.

They’re very common in the Colorado Desert area of California, particularly in Imperial Valley around the foothills of Mount Signal, but you’ll find them anywhere that an ancient lake or inland sea has dried out or dropped in level. These examples were formed when Lake Le Conte (also known as Lake Cahuilla) in California began drying out.

[Pic from article by SC Edwards in “Rocks -and- Minerals”, June 1934]

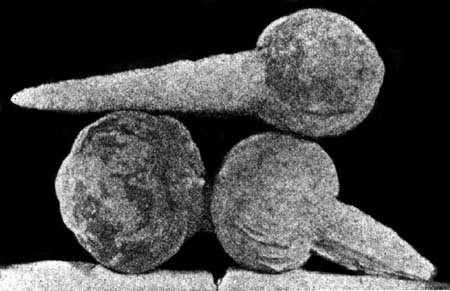

Despite the external appearance, the calcite crystals are oriented in a different manner in the head than in the tail. They’re definitely concreted and not formed by dripping water in the manner of a stalactite. They often have pebbles or pieces of silicified wood in the bulbous end, acting as a nucleus. You can see the concentric deposition rings in some of the spike heads below:

[pic from Oddities of the Mineral World - Van Nostrand Reinhold Company]

Depending on how calcited they are, they range from fragile to extremely hard. Certainly hard enough in some instances to be used as an implement if so desired, but use-wear would be evident if that is the case. They are sometimes found in burial contexts in California (both funerary and ritual) but with no evidence of having been used as tools.

These items, which you might mistake for some kind of club (if large) or charmstone (if small), are completely natural. They’re known as “sand spikes” and normally form in silt deposits as fine sand concretions cemented by calcite. The circumstances in which they are found may also falsely suggest that they have been deliberately buried in caches. Frequently you will find them in numerous clusters in secondary Pleistocene deposits, with the spike ends pointing away from an older formation they have been washed out of… sometimes hundreds of them, all uniformly oriented in a horizontal position, parallel to the boundary of an ancient shoreline.

They’re very common in the Colorado Desert area of California, particularly in Imperial Valley around the foothills of Mount Signal, but you’ll find them anywhere that an ancient lake or inland sea has dried out or dropped in level. These examples were formed when Lake Le Conte (also known as Lake Cahuilla) in California began drying out.

[Pic from article by SC Edwards in “Rocks -and- Minerals”, June 1934]

Despite the external appearance, the calcite crystals are oriented in a different manner in the head than in the tail. They’re definitely concreted and not formed by dripping water in the manner of a stalactite. They often have pebbles or pieces of silicified wood in the bulbous end, acting as a nucleus. You can see the concentric deposition rings in some of the spike heads below:

[pic from Oddities of the Mineral World - Van Nostrand Reinhold Company]

Depending on how calcited they are, they range from fragile to extremely hard. Certainly hard enough in some instances to be used as an implement if so desired, but use-wear would be evident if that is the case. They are sometimes found in burial contexts in California (both funerary and ritual) but with no evidence of having been used as tools.

Comment