BANNERSTONES... WHAT ARE THEY?

This feature reprinted from PREHISTORIC AMERICAN Vol. XXIV, No. 4, 1990 pages 14-16.

WILLIAM S. KOUP, ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO

What's it for? If you own a bannerstone, you've heard the question. Usually these are the first words uttered when a non collector examines a bannerstone. This is only natural, for who wouldn't want to know what use these beautiful artistic creations had. Unfortunately, a definitive answer is not yet available. Over the years, numerous researchers have tackled the problem of bannerstones, only to walk away from their efforts still not knowing for sure what they had been studying.

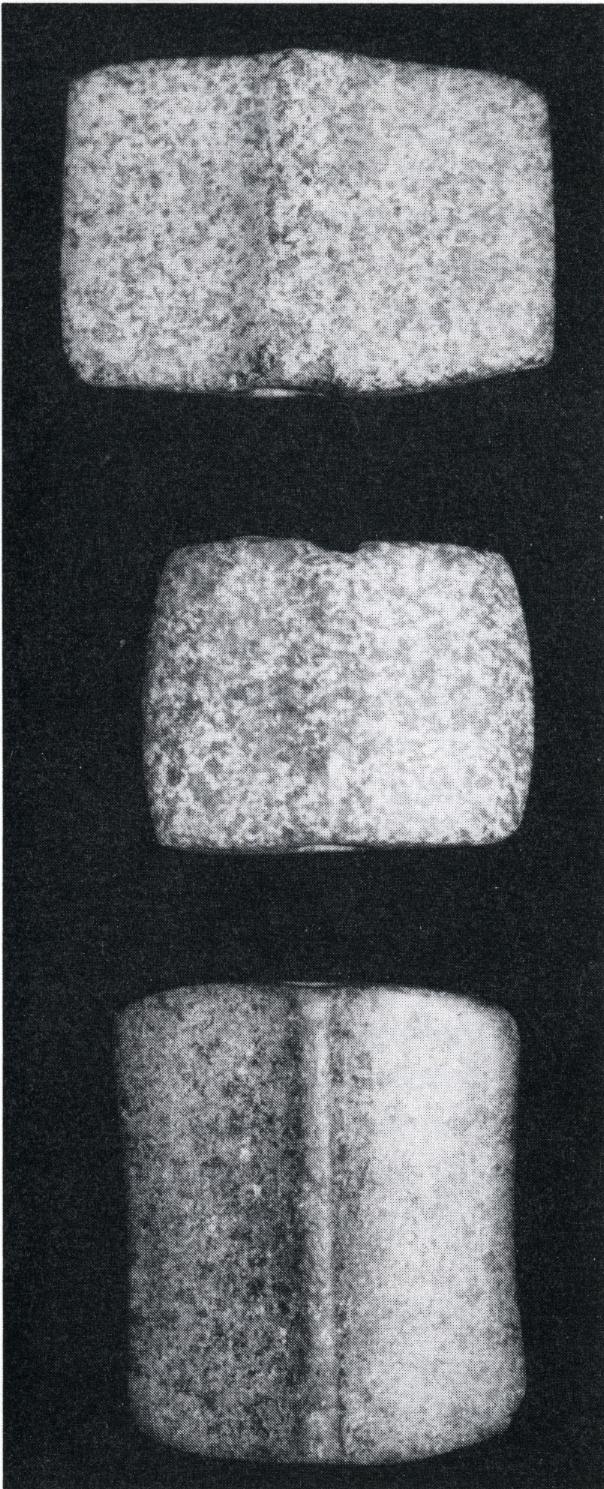

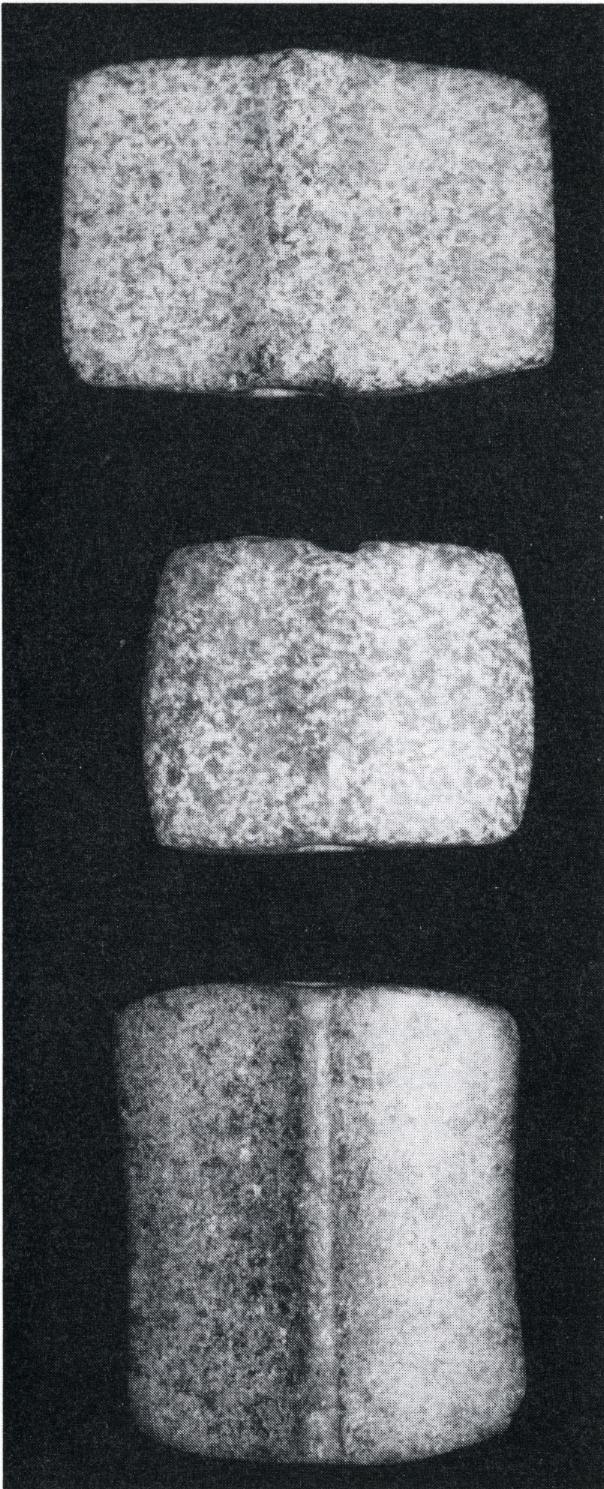

People have long been fascinated by bannerstones. Their greatest appeal is due to their desirability as an art form. Bannerstones were made in the Archaic period in a myriad of types and styles. Many of the ultimate-design specimens are true masterworks of non-representational art.

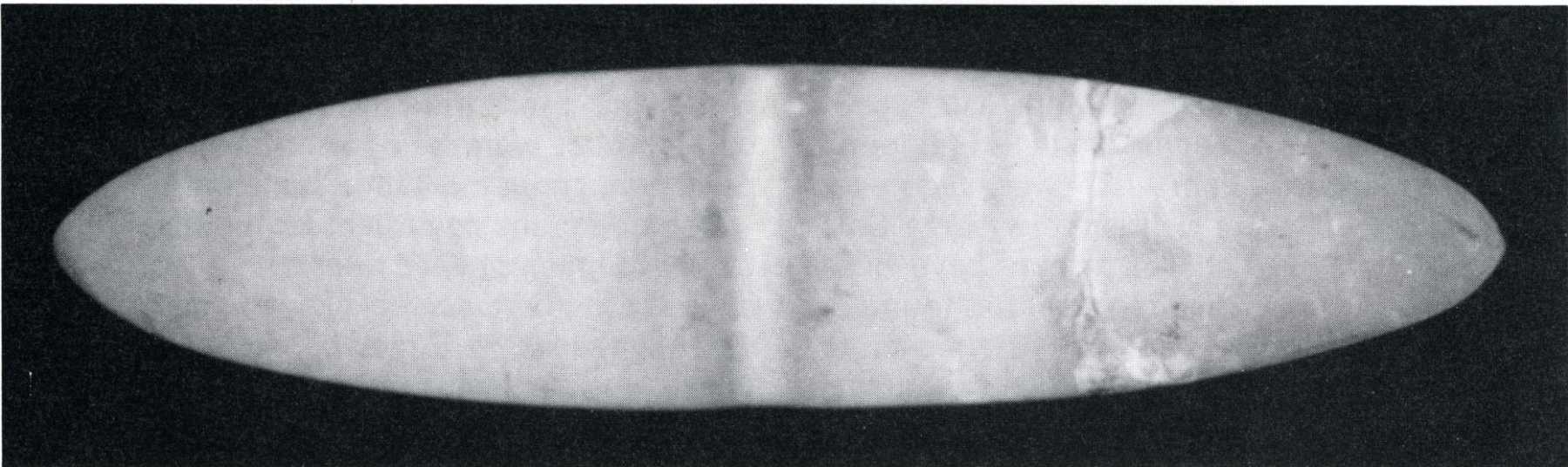

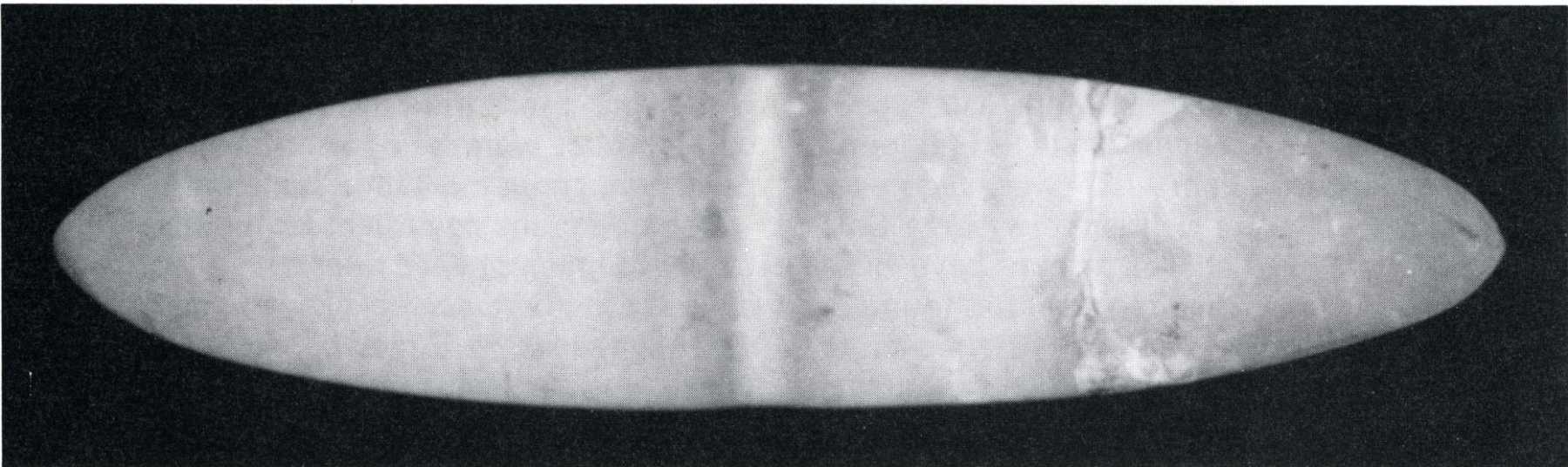

Who can resist the appeal of a quartz butterfly or the delicate symmetry of a highly developed double crescent? Yes, they are definitely artistic creations, but most of us are not satisfied to dismiss them as merely beautiful creations of prehistoric man. We have a great desire for a better understanding of these fascinating stone creations with the mysterious drilled holes.

The term bannerstone has been used for well over a century now. In Gates P. Thurston's 1890 Antiquities of Tennessee, he uses the term "bannerstone" when he states "they were doubtless, used as ornaments or symbols upon occasions of ceremony". Warren K. Moorehead uses the term in his 1900 Prehistoric Implements and states, "most if not all appear to have been designed either as ornaments, or emblems, or insignia. They are made from the handsomest available material and form conspicuous features in all large collections". Later, in the same publication, Moorehead states, "if we deal with facts absolutely we cannot tell for what purpose these (bannerstones) were used". By 1910, Moorehead was lumping bannerstones and other unexplained objects under the heading of "problematical" which defined, very loosely, means--"I don't know what it is?"

In 1921, John L Baer reported three crescent shaped slate bannerstones found in North Carolina. All three banners were mounted on the ends of slate shafts which were approximately one foot long. This lends credence to the early theories that bannerstones were ceremonial objects indicative of high rank. Unfortunately, there is little other evidence to support this conclusion.

In 1916, Clarence B. Moore published his findings from excavations done at Indian Knoll along the Green River in Ohio County, Kentucky. He found several bannerstones in association with antler hooks. From his findings Moore surmised that the bannerstones were net spacers and the hooks were netting needles. Based on Moore's findings Dr. George H. Pepper of the Heye Foundation suggested that the hooks and banner-stones were used in conjunction with each other as hair ornaments.

In 1938, William S. Webb returned to the Green River in Ohio County, Kentucky to conduct excavations at the Chiggerville Site, which was about three miles from Indian Knoll. In burial 44, Webb found a butterfly bannerstone made from what he describes as ferruginous chert and an atlatl hook. Based on Moore's work and his own work here and in Alabama, Webb proposed the theory that bannerstones were used as atlatl (spearthrower) weights placed between a handle and a bone or antler hook. This theory has been widely accepted by professional archaeologists and persists to this day as the most common explanation for the usage of bannerstones.

In 1939, Byron Knoblock published his monumental Bannerstones of the North American Indian. Although Knoblock's theories on antiquity and the evolution of all bannerstone forms from one primary form is dated and probably invalid, his system of placing all bannerstones within a named group is masterful. By studying the lines and planes of bannerstones, Knoblock developed a system of terminology where every bannerstone can be categorized and named. This has been invaluable to collectors and researchers alike due to the fact that we can all "speak the same language" in regards to bannerstones.

Knoblock stuck with the older theories on the usage of bannerstones. He believed they were ornamental or ceremonial objects. His conclusions were based partly on the fact that certain forms of bannerstones were usually made from exotic and beautiful material, such as ferruginous quartz or highly banded slate. He also felt that the time expended in making bannerstones, coupled with their fragile nature, would certainly negate their usage as utilitarian objects.

Throughout the 1940's, William S. Webb continued publishing reports on his findings in Kentucky and Alabama. In them, Webb further refined and expanded his theory that bannerstones were atlatl weights placed between an antler or bone hook and a handle. His research was so convincing that nearly all professionals accept his work as gospel. However, in her excellent and objective look into Webb's research, Mary L. Kwas has made some interesting observations. In looking at Webb's work at Indian Knoll she found that out of the total of 880 burials only 43 contained any kind of atlatl object. Of these 43 burials, only 2 contained a bannerstone, hook and handle. One burial contained a bar weight, hook and handle. Kwas also noted a very conspicuous lack of points found in the burials with atlatl objects. Perhaps, she pointed out, this was due to the usage of organic materials which did not survive. However, she noted that of the 45 burials with atlatl objects, only 5 had associated projectile points. Kwas seems to be saying that Webb's research should be considered more carefully and that his atlatl weight theory should not be taken as the ultimate answer to the usage of bannerstones.

In 1955, Byron Knoblock responded to Webb's theory by asking several pointed questions. Why are axes and celts far more plentiful than bannerstones? Why aren't arrowheads or spearpoints found in burials with atlatl parts? Why are many bannerstones so fragile and others so large and cumbersome? Why are banner-stones found in burials with women and children? He concludes his attack by rejecting the notion that bannerstones, birdstones and boatstones were all used as utilitarian objects.

Also, in her excellent overview of bannerstones, Mary L. Kwas summarized some of the experiments done with bannerstones attached to atlatls. J. Walker Davenport did experiments by moving bannerstones to different positions on the atlatl, but could find no help or hindrance one was or another. In 1960, Orville Peets felt that bannerstones helped balance the atlatl, but did not find that they increased distance. Clayton Mau experimented with various lengths of atlatls and found that certain lengths with precisely weighted stones could increase throwing distance. George Cole proposed in 1972 that weight may have been attached to the spear because he found a detrimental effect when weight was attached to the atlatl. In 1974, Calvin Howard found that increasing the atlatl and spear length could increase throwing distance, but adding weight decreased distance by 18 percent. Kwas reports on several other experiments with bannerstones, atlatls and spears that give variable and conflicting results that indicate the need for systematic experimentation. Until this is accomplished, the theory that bannerstones are indeed atlatl weights remains problematic.

Kwas reports that in 1973 Prudence Precourt wrote that bannerstones were atlatl weights and status symbols. Precourt states that only 3 percent of Archaic burials contain bannerstones, but 85 percent of the bannerstones found at Archaic sites were in non-burial contexts, thus indicating that a burial with a bannerstone was a status burial including those of women and children. Howard Winters in 1968 and Nan Rothschild in 1975 reached similar conclusions that bannerstones were status markers.

So, what are bannerstones, atlatl weights or ceremonial status objects? This writer feels strongly that bannerstones are indeed both. The Archaic Period lasted for at least 7000 years. It was within this long period that bannerstones first developed, rose to a climax and disappeared. There is a significant body of evidence suggesting that it is quite conceivable that early or less developed bannerstones were indeed intended to be used as weights. These forms might include, among others, tubes, humped, triangular, ball and other less elaborate forms of bannerstones.

Atlatls and the attached weights were the lifeblood of these hunters and gatherers. Probably no other possession contributed more to their survival than the atlatl. Perhaps over time the attached weight slowly became more elaborate, more decorative and more spiritual. Perhaps certain atlatls and attached weights were never intended to be used in a utilitarian way. It may have been that every family, clan or other unit possessed the power or luck needed to assure the survival of the owners. Over time these "special" bannerstones developed into the ultimate design specimens that we now consider among the highest artistic achievements of prehistoric man.

A modern analogy might be the highly decorative commemorative rifles and shotguns that have the highest degree of workmanship, special engravings, rare metals, exotic wood, fine detail, and special ammuni-tion. All of these features add nothing to the functionality of the weapon itself.

It is inconceivable that a large thin winged butterfly bannerstone would ever be used in a utilitarian way. Nor would the double crescents, notched ovates or many others. If these bannerstones were not special, symbolic atlatl weights, then they were certainly ceremonial objects of some sort. Of course these are merely the conjectures of this writer.

Much research is needed in the area of bannerstones. The area has been sorely neglected by the professional archaeological community. Most have jumped on the Webb bandwagon and have no intention of ever getting off. Fortunately there are a few researchers, like Mary L. Kwas and David Lutz, who refuse to wear the "Webb blinders" and have instead forged ahead with solid research and insightful thought.

Article used with permission by Bill Koup, Author

Duplicated from the “Resources” section of arrowheads.com and reproduced with permission.

This feature reprinted from PREHISTORIC AMERICAN Vol. XXIV, No. 4, 1990 pages 14-16.

WILLIAM S. KOUP, ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO

What's it for? If you own a bannerstone, you've heard the question. Usually these are the first words uttered when a non collector examines a bannerstone. This is only natural, for who wouldn't want to know what use these beautiful artistic creations had. Unfortunately, a definitive answer is not yet available. Over the years, numerous researchers have tackled the problem of bannerstones, only to walk away from their efforts still not knowing for sure what they had been studying.

People have long been fascinated by bannerstones. Their greatest appeal is due to their desirability as an art form. Bannerstones were made in the Archaic period in a myriad of types and styles. Many of the ultimate-design specimens are true masterworks of non-representational art.

Who can resist the appeal of a quartz butterfly or the delicate symmetry of a highly developed double crescent? Yes, they are definitely artistic creations, but most of us are not satisfied to dismiss them as merely beautiful creations of prehistoric man. We have a great desire for a better understanding of these fascinating stone creations with the mysterious drilled holes.

The term bannerstone has been used for well over a century now. In Gates P. Thurston's 1890 Antiquities of Tennessee, he uses the term "bannerstone" when he states "they were doubtless, used as ornaments or symbols upon occasions of ceremony". Warren K. Moorehead uses the term in his 1900 Prehistoric Implements and states, "most if not all appear to have been designed either as ornaments, or emblems, or insignia. They are made from the handsomest available material and form conspicuous features in all large collections". Later, in the same publication, Moorehead states, "if we deal with facts absolutely we cannot tell for what purpose these (bannerstones) were used". By 1910, Moorehead was lumping bannerstones and other unexplained objects under the heading of "problematical" which defined, very loosely, means--"I don't know what it is?"

In 1921, John L Baer reported three crescent shaped slate bannerstones found in North Carolina. All three banners were mounted on the ends of slate shafts which were approximately one foot long. This lends credence to the early theories that bannerstones were ceremonial objects indicative of high rank. Unfortunately, there is little other evidence to support this conclusion.

In 1916, Clarence B. Moore published his findings from excavations done at Indian Knoll along the Green River in Ohio County, Kentucky. He found several bannerstones in association with antler hooks. From his findings Moore surmised that the bannerstones were net spacers and the hooks were netting needles. Based on Moore's findings Dr. George H. Pepper of the Heye Foundation suggested that the hooks and banner-stones were used in conjunction with each other as hair ornaments.

In 1938, William S. Webb returned to the Green River in Ohio County, Kentucky to conduct excavations at the Chiggerville Site, which was about three miles from Indian Knoll. In burial 44, Webb found a butterfly bannerstone made from what he describes as ferruginous chert and an atlatl hook. Based on Moore's work and his own work here and in Alabama, Webb proposed the theory that bannerstones were used as atlatl (spearthrower) weights placed between a handle and a bone or antler hook. This theory has been widely accepted by professional archaeologists and persists to this day as the most common explanation for the usage of bannerstones.

In 1939, Byron Knoblock published his monumental Bannerstones of the North American Indian. Although Knoblock's theories on antiquity and the evolution of all bannerstone forms from one primary form is dated and probably invalid, his system of placing all bannerstones within a named group is masterful. By studying the lines and planes of bannerstones, Knoblock developed a system of terminology where every bannerstone can be categorized and named. This has been invaluable to collectors and researchers alike due to the fact that we can all "speak the same language" in regards to bannerstones.

Knoblock stuck with the older theories on the usage of bannerstones. He believed they were ornamental or ceremonial objects. His conclusions were based partly on the fact that certain forms of bannerstones were usually made from exotic and beautiful material, such as ferruginous quartz or highly banded slate. He also felt that the time expended in making bannerstones, coupled with their fragile nature, would certainly negate their usage as utilitarian objects.

Throughout the 1940's, William S. Webb continued publishing reports on his findings in Kentucky and Alabama. In them, Webb further refined and expanded his theory that bannerstones were atlatl weights placed between an antler or bone hook and a handle. His research was so convincing that nearly all professionals accept his work as gospel. However, in her excellent and objective look into Webb's research, Mary L. Kwas has made some interesting observations. In looking at Webb's work at Indian Knoll she found that out of the total of 880 burials only 43 contained any kind of atlatl object. Of these 43 burials, only 2 contained a bannerstone, hook and handle. One burial contained a bar weight, hook and handle. Kwas also noted a very conspicuous lack of points found in the burials with atlatl objects. Perhaps, she pointed out, this was due to the usage of organic materials which did not survive. However, she noted that of the 45 burials with atlatl objects, only 5 had associated projectile points. Kwas seems to be saying that Webb's research should be considered more carefully and that his atlatl weight theory should not be taken as the ultimate answer to the usage of bannerstones.

In 1955, Byron Knoblock responded to Webb's theory by asking several pointed questions. Why are axes and celts far more plentiful than bannerstones? Why aren't arrowheads or spearpoints found in burials with atlatl parts? Why are many bannerstones so fragile and others so large and cumbersome? Why are banner-stones found in burials with women and children? He concludes his attack by rejecting the notion that bannerstones, birdstones and boatstones were all used as utilitarian objects.

Also, in her excellent overview of bannerstones, Mary L. Kwas summarized some of the experiments done with bannerstones attached to atlatls. J. Walker Davenport did experiments by moving bannerstones to different positions on the atlatl, but could find no help or hindrance one was or another. In 1960, Orville Peets felt that bannerstones helped balance the atlatl, but did not find that they increased distance. Clayton Mau experimented with various lengths of atlatls and found that certain lengths with precisely weighted stones could increase throwing distance. George Cole proposed in 1972 that weight may have been attached to the spear because he found a detrimental effect when weight was attached to the atlatl. In 1974, Calvin Howard found that increasing the atlatl and spear length could increase throwing distance, but adding weight decreased distance by 18 percent. Kwas reports on several other experiments with bannerstones, atlatls and spears that give variable and conflicting results that indicate the need for systematic experimentation. Until this is accomplished, the theory that bannerstones are indeed atlatl weights remains problematic.

Kwas reports that in 1973 Prudence Precourt wrote that bannerstones were atlatl weights and status symbols. Precourt states that only 3 percent of Archaic burials contain bannerstones, but 85 percent of the bannerstones found at Archaic sites were in non-burial contexts, thus indicating that a burial with a bannerstone was a status burial including those of women and children. Howard Winters in 1968 and Nan Rothschild in 1975 reached similar conclusions that bannerstones were status markers.

So, what are bannerstones, atlatl weights or ceremonial status objects? This writer feels strongly that bannerstones are indeed both. The Archaic Period lasted for at least 7000 years. It was within this long period that bannerstones first developed, rose to a climax and disappeared. There is a significant body of evidence suggesting that it is quite conceivable that early or less developed bannerstones were indeed intended to be used as weights. These forms might include, among others, tubes, humped, triangular, ball and other less elaborate forms of bannerstones.

Atlatls and the attached weights were the lifeblood of these hunters and gatherers. Probably no other possession contributed more to their survival than the atlatl. Perhaps over time the attached weight slowly became more elaborate, more decorative and more spiritual. Perhaps certain atlatls and attached weights were never intended to be used in a utilitarian way. It may have been that every family, clan or other unit possessed the power or luck needed to assure the survival of the owners. Over time these "special" bannerstones developed into the ultimate design specimens that we now consider among the highest artistic achievements of prehistoric man.

A modern analogy might be the highly decorative commemorative rifles and shotguns that have the highest degree of workmanship, special engravings, rare metals, exotic wood, fine detail, and special ammuni-tion. All of these features add nothing to the functionality of the weapon itself.

It is inconceivable that a large thin winged butterfly bannerstone would ever be used in a utilitarian way. Nor would the double crescents, notched ovates or many others. If these bannerstones were not special, symbolic atlatl weights, then they were certainly ceremonial objects of some sort. Of course these are merely the conjectures of this writer.

Much research is needed in the area of bannerstones. The area has been sorely neglected by the professional archaeological community. Most have jumped on the Webb bandwagon and have no intention of ever getting off. Fortunately there are a few researchers, like Mary L. Kwas and David Lutz, who refuse to wear the "Webb blinders" and have instead forged ahead with solid research and insightful thought.

Article used with permission by Bill Koup, Author

Duplicated from the “Resources” section of arrowheads.com and reproduced with permission.

Comment